What I've learned about publishing as a debut author

/Agents are heroes

I am in love with each and every one of them. I know, from a distance, that they can seem like impenetrable gatekeepers but they are passionate advocates for good writing, work ungodly hours for work that they believe in and have no guarantee of financial reward. Sound familiar? Like writers, they too have to go through the precarious and heart-thumping process of submissions, rejections and deals. Agents not only help hone your work and protect your rights, but are a great sounding board throughout the entire journey. But most importantly they believe in, and fight for, books and writers. If you meet one, you should look them in the eye and say thank you. *A deep bow to Jenny Savill.

Book people are incredibly generous

The generosity of the industry has taken my breath away. Influential editors and publicists from other publishing houses have praised A Thousand Paper Birds on social media and encouraged others to read it – and I’ve seen them do it with other debuts too. Why? Because they are passionate about books that they love whether it’s from their imprint or not. There are so many inspiring, authentic, brilliant people in this industry – brains as big as planets (a big wave to Georgina Moore and Alison Barrow!). The same is true of authors. If they believe in your work, they will shout about it from the rooftops. Being published for the first time is a giddy ride and it’s helpful to meet other authors on the rollercoaster. Having received so much support, I’m keen to help upcoming writers. It’s one massive chain of ink-stained hands and I love being a part of it. I truly believe this industry contains some of the best human beings on the planet.

It is a team effort

After years of solitary writing, it has been a privilege to collaborate with the team at Bloomsbury. They are brilliant at what they do. From my sublimely smart editor to my sensitive and astute copy-editor, through to my designer and the publicity, marketing and digital teams, they’ve all been fighting my corner and helping the book be the best it can be. What a freakin’ honour.

It’s not true that you need to be well connected

I got my first agent through the slush pile (most writers do). After losing him, I went to the Festival of Writing and left with 8 agents interested in representing. I put in the graft. I said hello. At my first meeting with my publicist, she asked if I had any media contacts and my awkward answer was ‘not a sausage.’ But we sent out the proofs and a few people really liked it. They then told other people who told other people and suddenly we had momentum. I will be forever indebted to the authors, reviewers, bloggers and readers who have championed Paper Birds. And some of these ‘strangers’ have become friends. In an overcrowded market you need people singing about your book. The beauty is that one voice can become a chorus.

Publishing is a vast eco-system

Pre-publication, most writers learn about agents and publishers, but the vitality of the industry is dependent on a much larger eco-system that includes mentors and editors, literary scouts, translators, bloggers, vloggers, reviewers and most importantly booksellers. Yes, that person behind the till at your local bookshop is the king or queen you should worship. Booksellers can make or break a book. If they buy one copy and shelve it in alphabetical order (you will normally find ‘U’ in the darkest corner) there’s not much chance of that book being sold and the shop ordering more. But if they highlight it in a table or window display, things are very different. Waterstones in Richmond did a gorgeous window for A Thousand Paper Birds. It became their biggest selling hardback for 4 weeks, almost outselling their bestselling paperback. Get to know your local booksellers. Buy from them. Give them chocolate. They make all the difference.

Your first chapter remains as important as ever

Reviewers and bloggers receive SACKS of books weekly. There is no way they can read them all. A few reviewers have told me that they read the first page and if it’s not sparked their interest, they move onto the next one. The sheer volume prevents them doing it differently and rightly they want to spend their energy and time on books they love. Many of them are freelancers or fitting reviews in between the day job and yet still they will go out of their way to make a difference. So work hard on your pitch and your first chapter. Getting past that ‘sack-pile’ is quite a hurdle.

You will, at times, be terrified

A couple of weeks before publication I said to my friend, ‘How can I stop this?’ Yes, those were my words after twenty years of perseverance because suddenly it was too exposing and far too unknown. I spent the first three months completely out of my comfort zone. I was interviewed for ITV news, pranced about in photoshoots, did many Q&A events/ readings, gave a keynote speech and later did a live 30-minute radio interview for America. It’s quite something moving from the private act of writing to the public stage. It requires completely different mind-sets. As hard as it is to come out of your shell, it can also then be difficult to withdraw again and deepen your focus. You almost need to separate these two identities – and with all your might protect the quieter one that is aching to write. Events are wonderful – and it’s an honour to be invited to talk about your work – but they are also exhausting. They will, at times, scare the life out of you, but they will also stretch you into a bigger person than you knew you could be. And to be honest, despite the nerves, I would return home, yelling I LOVED IT!

You will juggle many, many balls

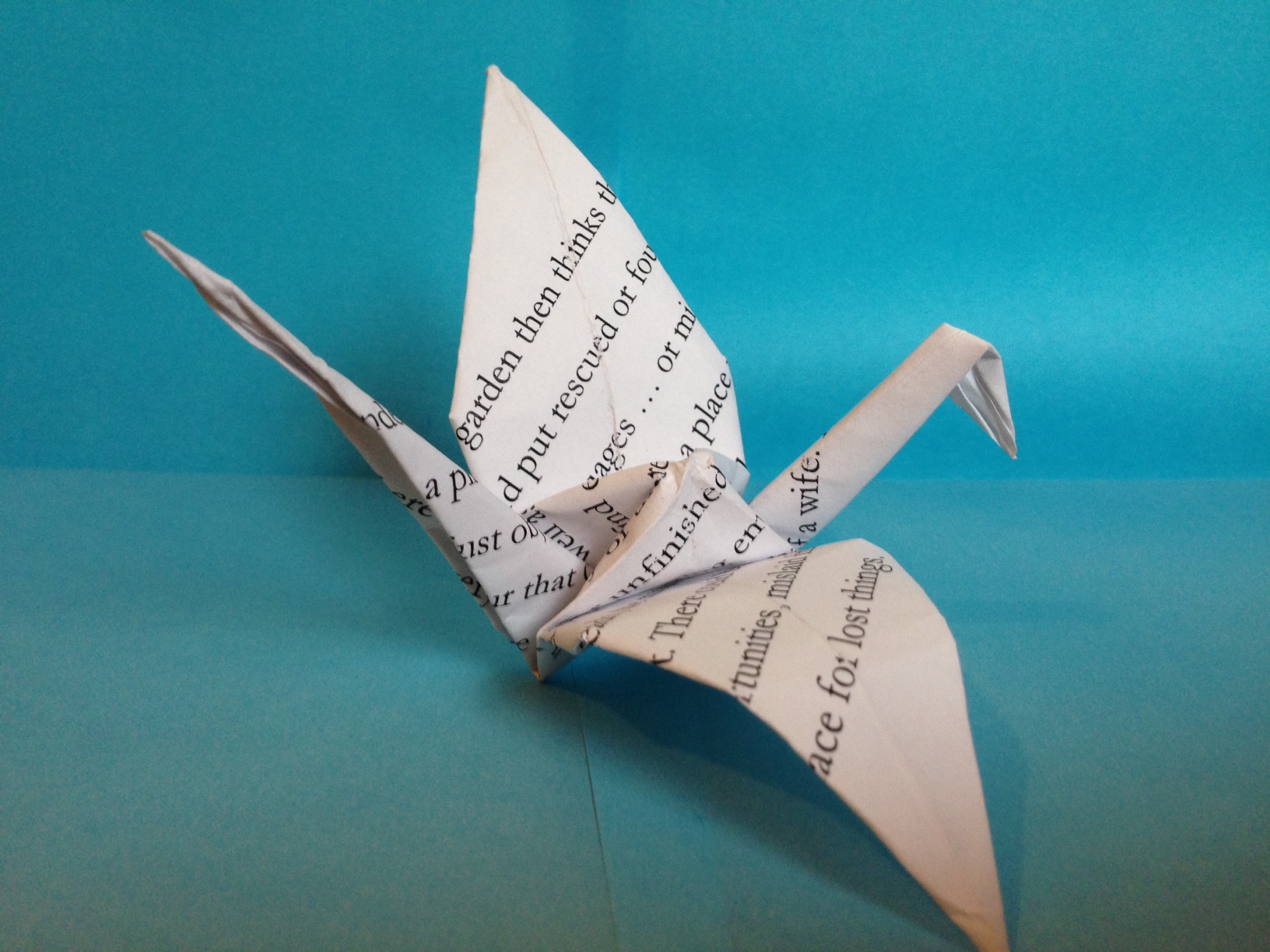

You will be promoting one book while writing another and perhaps pitching a third. You will be answering Q&As for various journals and writing articles. You will be reading all the new books that have been sent to you for endorsement as well as trying to keep up with your usual favourites. You will also be setting yourself up as a business, sorting out foreign royalty forms, and for me, having to work out 7-years of expenses for my tax return (HIDEOUS). While doing this you may also be juggling a day job and caring for children (or the sick or elderly) – and if you’re really crazy folding HUNDREDS of paper birds for displays and promotions. Anxiety is, unsurprisingly, common. Suddenly the writer is being pushed and pulled in several directions. While writing to deadline you may well have to sacrifice personal hygiene. But to survive, at some point you will need to learn how to say ‘no’ or at least ‘not now.’ And you will need to take responsibility for your own well-being by putting in support mechanisms (for me, it was yoga). I thought that success would allow me more time to write, but actually there’s been less. There gets a point where you have to prioritise writing your next book over all the chaos.

Social Media is both friend and foe

My timeline is full of stunningly brilliant people, fantastic books and new friends who make me laugh on days when it feels like the world is going to hell in a handcart. On twitter, I’ve found my tribe, but beware, it is a major time-sucker. Also, if there are days when you’re struggling with self-doubt, it can be tricky to take in the constant barrage of big advances and bestsellers. You must do everything you can not to compare yourself to others. The truth is that there will always be people doing ‘better’ and ‘worse’ than you. (And remember, a published writer isn’t necessarily more talented than an unpublished one – it’s so dependent on timing and market.) All you can do is focus on your own journey. Twitter is also a great way to find out who is who and how it all works: the eco-system in all its glory.

There are still set-backs

You would think that after getting through agent rejections and years of perseverance that once you reach publication everything is golden. But that gold is sometimes honey, sometimes treacle and sometimes actually a bit pissy. There are many books of the month and end of the year lists, debuts to watch out for, longlists, shortlists, book club selections and promotions. When you are listed or selected for something, it is an amazing feeling. When you don’t, it can feel rotten. All of the above betters your chance of getting a second book deal, so in that context it can feel quite stressful. There have been days when I’ve wanted to google ‘where can I buy extra layers of skin?’ But you can’t buy that resilience, you can only earn it. My rule is that I’m allowed to wail and beat my chest for one day but for one day only. The next morning, I roll up my sleeves and face the most compelling challenge of all – how to be a better writer than I was yesterday. Everything else isn’t in my power. It is just noise.

The reader is the most important ingredient of all

Stupidly, I didn’t share my work with many people pre-publication – mostly, out of terror. So this year has been a revelation. Every day I receive messages from readers saying how much A Thousand Paper Birds has moved them. I had no idea how much that would mean to me. Unbelievably I hadn’t got my head around the fact that it is the reader who breathes life into the characters and makes the story live. Now that my characters exist in others’ heads they have become real (and I hear they are sometimes glimpsed in the book’s location, Kew Gardens). The reader is the true alchemist. The true creator. This has been my biggest and most humbling lesson of all.

Remember why you’re doing this

After Paper Birds was published, a famous author wrote to me saying, I should try to stay ‘grounded and clear-headed. Don’t get confused by events one way or the other.’ I have found this advice to be invaluable. You can so easily be swayed by great reviews then knocked down the next day with disappointment. It is the way to madness. And the biggest joke, once you’re published, is that you realise that there is no finishing line. After years of striving, you reach the top of that glorious, much-longed-for hill and see that you are only at the start of a vast mountain range. So you have to love the journey itself – the actual writing. To stay curious about your characters. To strive to tell the truth. To fail and start again. To be in love with the work itself. To write with humility and the hunger to learn. The more I understand about both this industry and the craft, the more I realise that I am a mere novice.

But isn’t that a fascinating place to be? My famous author finished his advice by saying, ‘Crack open a bottle of champagne …. And send a quiet thank you to the realms that deserve it.’ It’s important not to forget the magic. The mystery that you stumble on at three in the morning when you’re been slogging away for hours and then all of a sudden the right words fall through the sky in the right order and you are merely taking dictation. In that instant, the book market fades into the background as a temporary, fickle thing. The ego that fretted about what to wear to that event dissolves and there is just the essence – the listening. The strange act of writing becomes the beating heart of everything.

And this is what I can tell you. At that point it doesn’t matter if you’re published or unpublished, we’re all on the same daunting and heroic journey. The stories we tell each other impacts us all. They shape how we respond to the world and what we create in it. In these tumultuous times we need stories more than ever. If you are a writer, I salute you. It takes a certain amount of courage, of innocent madness, to retain a state of wonder, tohelp us all see clearer and to be more empathic. And sometimes, just sometimes, some of us might imagine alternative ways of walking through this world that makes everything brighter.